Mobile biometric devices (MBDs) capable of both enrolling individuals in databases and performing identification checks of subjects in the field are seen as an important capability for military, law enforcement, and homeland security operations. The technology is advancing rapidly. The Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate through an Interagency Agreement with Sandia sponsored a series of pilot projects to obtain information for the first responder law enforcement community on further identification of requirements for mobile biometric device technology. Working with 62 different jurisdictions, including components of the Department of Homeland Security, Sandia delivered a series of reports on user operation of state-of-the-art mobile biometric devices. These reports included feedback information on MBD usage in both operational and exercise scenarios. The findings and conclusions of the project address both the limitations and possibilities of MBD technology to improve operations. Evidence of these possibilities can be found in the adoption of this technology by many agencies today and the cooperation of several law enforcement agencies in both participating in the pilot efforts and sharing of information about their own experiences in efforts undertaken separately.

…

1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Background

The first responder law enforcement community is increasingly interested in mobile biometric devices (MBDs)—handheld devices that gather fingerprint, iris, facial, and other biological information about subjects in the field and communicate with remote databases to rapidly provide information that can help identify the subject. To help the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate (DHS S&T) formulate future requirements for MBD for first responders, Sandia National Laboratories in July 2010 (under HSHQPM-09-X00028-2) undertook the Mobile Biometrics Device Test and Evaluation (MBD T&E) project.

Approach

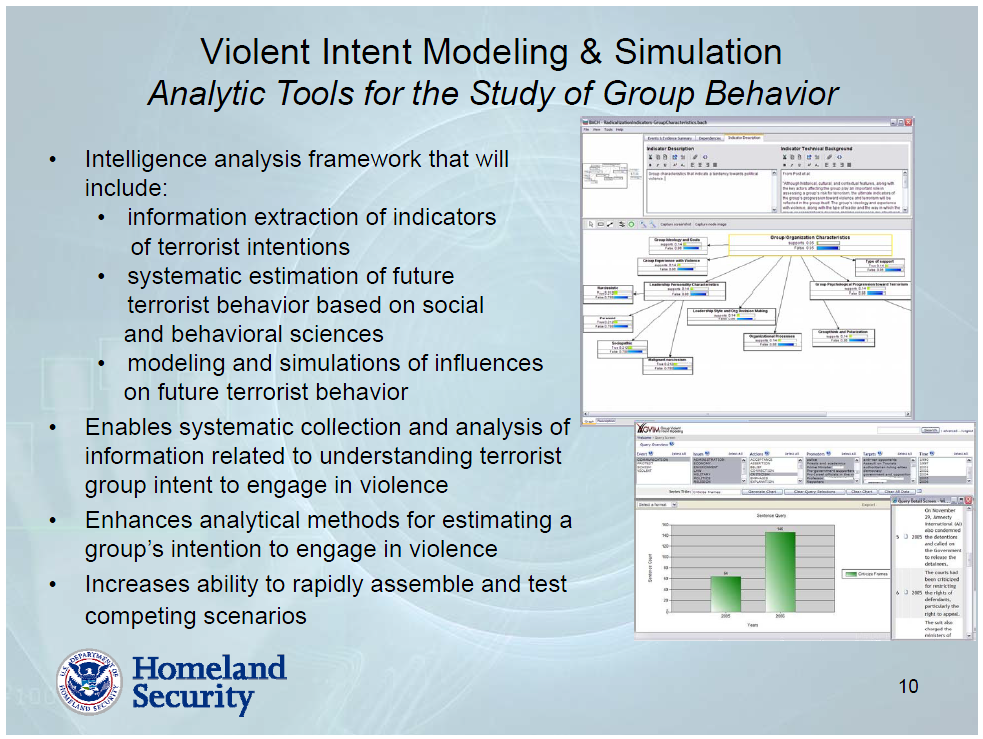

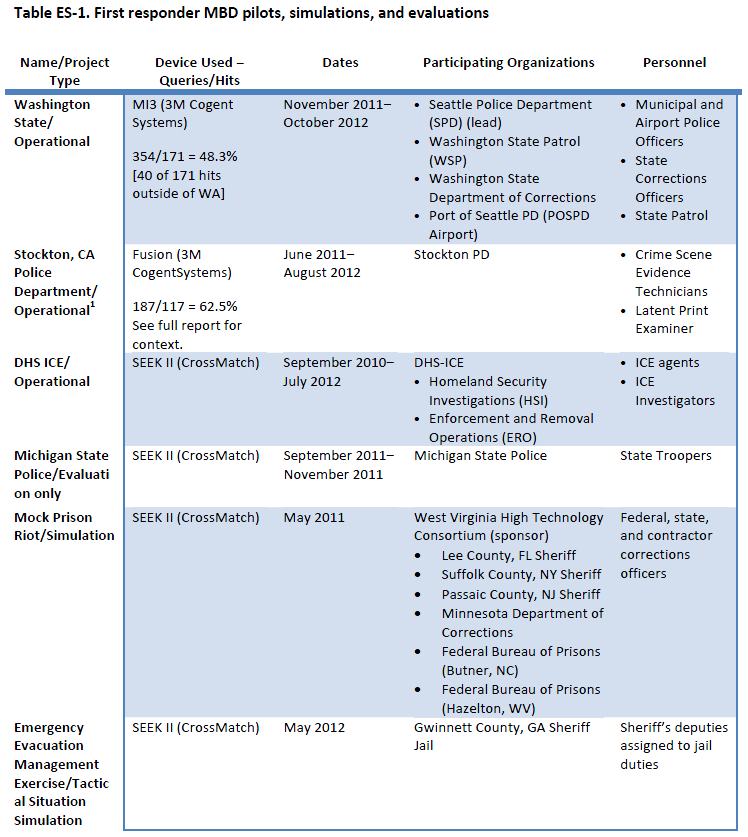

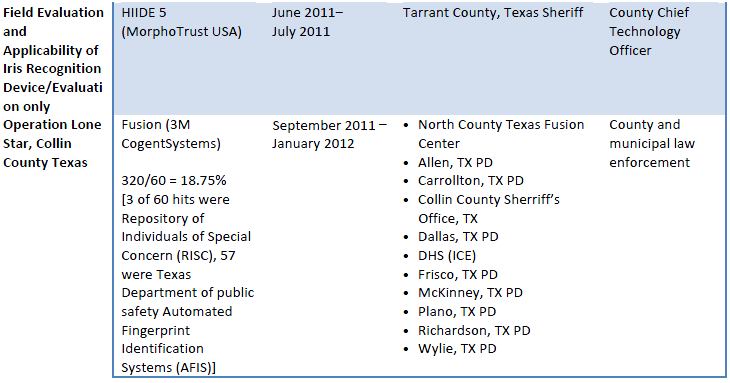

This project ultimately led to a variety of operational end-user evaluations on state-of-the-art biometric devices in collaboration with a number of federal, state, local, and specialized law enforcement agencies, as shown in Table ES-1. The objective of these evaluations was to test the MBD in operational environments and gather user feedback on performance and usage of, and potential improvements to, the devices to increase their value to the first responder law enforcement community.

![mbd-study-1]()

![mbd-study-2]()

Findings

The MBD T&E project acquired substantial information and data on the current use of mobile identification technologies in the field by first responder law enforcement jurisdictions in the United States. A summary of these findings follows:

1. MBD technology is considered important to operations and officer efficiency.

From the first responder perspective, introducing state-of-the-art MBD technologies into operations in the form of limited test and evaluation activities is important to understanding the possibilities and limitations of current and emerging biometric technologies. This perspective is underscored by the fact that more than 50 jurisdictions expressed interest in participating in the MBD T&E pilot project and that many of these jurisdictions had already decided to introduce mobile identification (ID) technology into their field operations. Moreover, the agencies that had sufficient infrastructure to participate found the pilot experience extremely helpful, as indicated in the following email of January 17, 2013, from Assistant Chief of Police Paul McDonagh of the Seattle Police Department:

“…The Pilot Project surrounding the Mobile Identification Device funded under DHS was a success on a number of fronts.

First it highlighted the emerging technology, and how the technology could be control for access to protected information. While we tested one product, in our group discussions we determined any future devices and the vendors can be varied to fit the task assignment of the officers – provided the specifications to communicate from each device to legacy system match the technical specifications.

Different size and capabilities of the devices are required for different police functions: bike officers, patrol officers, detectives. As example this became apparent with our pilot devices. They were a little larger than convenient to carry while operating on a bicycle and smaller units would provide them with the same capability. However, the officers would use the larger devices if they did not have access to the smaller sizes.

This highlights the next point: this pilot reduced the officer out of service time to determine identity. Officers stayed in the field where they can continue to work higher crime areas and back up other officers. This has a larger impact on police services in the future as we face reduced staffing and increasing demands for police services….”

Officers involved in this pilot believe this is a valuable tool that when put into place, with the necessary policy and procedures for use, will greatly enhance officer safety and effectiveness in the field.

The project was, for our purposes, successful and we are researching how we can provide this capability to our officers long term.

2. MBDs are used by first responders today in some jurisdictions; these jurisdictions represent a small percentage of total law enforcement agencies.

MBDs have been used since as early as 2002 by law enforcement state and local first responders. Current regular use of MBDs relies on intermediate communication links and Wi-Fi proximity to either Blackberries or patrol car mobile data terminals. [See “The Evaluability Assessment of Mobile Automated Fingerprint Identification System (AFIS)” at https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/afis.pdf] These devices are limited to a single modality (fingerprint). However, the major providers of these devices also offer the capability to display mug shots and criminal history information associated with a fingerprint directly on the device or on the intermediary communications display. These devices have also demonstrated the capability of accessing authoritative criminal justice databases from the field, such as the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI’s) Repository of Individuals of Special Concern (RISC). Day-to-day use of facial recognition capability from the field appears to remain limited and confined to only a few jurisdictions. Facial recognition, however, is available through alternate communication means, such as transfer of JPEG or other files from cell phone or social networking sites. The jurisdiction leading the implementation of facial recognition as a daily tool and facilitating adoption by other jurisdiction is the Sheriff’s Office of Pinellas County, Florida.

State and local officials see the advantages of expanding the capability of mobile wireless devices to permit identity checks from anywhere in the field, outside of the range of a patrol vehicle or intermediary communication devices. However, they stress that the ultimate utility of such capability resides in access to authoritative criminal justice/terrorist databases, such as FBI Integrated Automated Fingerprint Identification System (IAFIS), and the forthcoming FBI Next Generation ID. The Washington State pilot had access to a regional data repository: the Western States Identification Network covering seven western States. The Collin County, Texas, pilot had access to the FBI RISC database, as well as the database of the Texas Department of Public Safety.

Perhaps the heaviest user of MBD field identification is the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Office (LASO), which also manages the Los Angeles Regional Identification System (LACRIS). LASO reports that between July 1, 2006, and January 15, 2013, more than 40 jurisdictions within LA County using some 2,500 devices (BlueCheck) conducted 326,342 mobile identification searches that garnered hits or matches in 121,995 instances. LASO did not keep records on the disposition of identifications in the field (detain or release subject).

Additional information was provided from the Michigan State Police (MSP). That department deployed a number of the IBIS Extreme MBDs and reported that for seven months in 2012, troopers conducted 778 roadside searches, with 293 identifications. Like LASO, the MSP does not keep specific records on the disposition of identifications in the field. MSP did provide the following perspective on the advantages of mobile ID capability when asked to address return on investment:

“…We do not have detailed statistics on how many times this roadside identification saved the officer from transporting to a live scan device when not needed. We also don’t have detailed information on how many times identification was made to a wanted person which may have been released if the officer did not have a Mobile Identification device. From our perspective 778 times last year this device assisted the officer in either saving drive time, taking an officer off the road when not needed or identifying a person that had a warrant or needed to be detained based on information that was returned because of Mobile ID. If positive identification is needed without Mobile ID would easily take an officer out of service for an hour per incident. There are additional costs related to the vehicle, gas and ware. The cost of releasing a person with a warrant is not easily measurable and in some cases this could easily justify the costs of Mobile ID…”

3. MBD technologies can support efforts to prevent terrorism, but DHS first responder state and local partners require better access to data repositories containing information on known or suspected terrorists.

DHS components most directly engaged in the mission to prevent and identify the entry into the United State of terrorists and other threat individuals or groups participated in the MBD T&E pilot project to varying degrees. The initial use of MBD under this project—to support DHS Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE) operations (Southwest Border Intelligence Coordination Unit) in detention centers—led DHS ICE to plan for MBD use in future operations. Toward the end of the project, ICE was considering introduction of MBDs in each of their detention facilities, an effort being coordinated with the ICE Biometrics Identification Transnational Migration Alert Program (BITMAP) program. In addition, Operation Tormenta, conducted by the Customs and Border Protection Office of Border Patrol (CBP OBP), provided information on future mobile identification requirements, and the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG) continues to evaluate MBDs for both enrollment and identification in maritime environments.

4. MBD Technology Pilot preparation is complex.

Initial planning, coordination, staging, and training are essential to a successful pilot program. Even in cases that benefited from DHS partner “champions,” the process involves complete awareness and support throughout the entire organization, from first responder law enforcement agency management to the IT managers to the officers/agents using the device. However, overcoming these challenges—which requires understanding all stakeholder equities, with special detailed attention to technical questions and policy concerns—can potentially provide a payback by preparing agencies to evolve into institutionalized test beds for future biometric technologies. This lesson reflects the large issue of developing and implementing a reliable operational test and evaluation of biometric technologies discussed in the recent report of the National Academy of Sciences on Biometric Recognition: Challenges and Opportunities 2010.

5. MBD technology can improve field operations and achieve cost savings for departments and agencies.

DHS components and partners believe MBD can improve forensics in the field and potentially save time and reduce costs in both the homeland security and criminal justice processes. For example, stakeholders have noted MBD’s potential for improving “forward echelon” reporting on processing aliens of special interest where a 24-hour limit on detention is a factor; point of encounter/identity adjudication for large groups of apprehended aliens to determine most efficient transportation routing; book and release in the field to avoid transport to detention facilities for non-felonies; and special event management. Nonetheless, certain DHS CBP components have noted MBD capability gaps in after-action reports. DHS partners are pursuing MBD technical research on the value communicating latent prints images directly from the field to data repositories for much earlier investigative actions up to, but not including, arrest. Use of MBD technology also requires subsequent Latent Print Examiner review and matching of the print images obtained by the mobile device.

6. MBD technologies for subject/suspect/detainee enrollment in the field is currently of definite interest to a limited number of certain law enforcement first responder stakeholders who have also identified a need for a truly integrated MBD that uses fingerprint, facial recognition, iris recognition, and voice recognition technologies. Many DHS enforcement components are interested in the use of MBD for enrollment as well as for identification at the “point of encounter” in the field of subjects in the field. However, attitudes are mixed. Specifically, after evaluating the SEEK II designed specifically for enrollment operations, the Michigan State Police indicated they did not plan to implement such a capability in future operations, but were very well satisfied with the capability to conduct identity checks in the field. In contrast, via email received on January 16, 2013, the Los Angeles County Regional Identification System Manager states:

“LA is VERY interested in enrollment in the field. One example, we would like to conduct a complete field booking (capturing demographics and biometrics – fingerprints with appropriate subject acquisition profile level, photographs, iris, voice, on a portable device) and release on their own recognizance, when appropriate, without the officer having to take the suspect to a brick and mortar booking location.”

Conclusions

- Near-term efforts (five years or less) should focus on improving fingerprint collection in the field at the point of encounter with subjects or suspects.

- Enrollment in an actual field environment is of limited interest to the state and local first responder law enforcement community. However, DHS components such as the USCG (Mona Pass) and CBP OBP (Tormenta) expressed interest in at least monitoring this capability and participating in pilot activities with these types of devices. DHS ICE also expressed interest and participated at various stages of the pilot, but confined their use of MBDs associated with this project inside the United States (SEEK II) to the “ID only” function.

- The quality of cell phone cameras makes both facial recognition and iris recognition a real potential for field operations in the future. Nonetheless, integrating biometric modalities other than fingerprints in the context of mobile operations is problematic. Some jurisdictions are using facial recognition and incorporating iris recognition into their booking systems, but these modalities appear restricted to highly controlled environments.

- Officer safety will remain the most critical factor in a jurisdiction’s decision on whether to adopt mobile ID with expanded modalities.

- A separate report that documents use of MBD use in crime scene investigation and imaging of latent prints may be of value to crime scene first responders (Evidence Technicians). The context for such “cutting edge” crime scene mobile ID application should recognize the priority assigned to latent print searches by large (state and federal) AFIS systems.

- Use of MBD in emergency evacuation scenarios involving jails or jail environments—the West Virginia “Mock Prison Riot” and Gwinnett County, Georgia, jail emergency evacuation exercise—were documented in separate contract reports under this project.